The Rumor Mill: Was Bad Bunny Sued By FCC Over Super Bowl Performance?

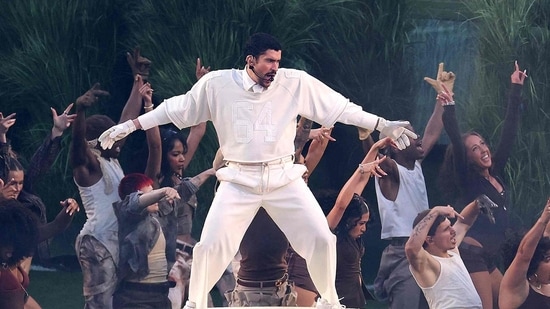

The electrifying energy of the Super Bowl halftime show often ignites conversations, but few performances have sparked as much controversy and misinformation as Bad Bunny's appearance. In the immediate aftermath, a wave of social media posts and news fragments circulated, leading many to believe that Bad Bunny was sued by the FCC and slapped with an astronomical $10 million fine. This narrative quickly gained traction, fueling outrage and debate across various platforms.

However, the truth, as often happens in the age of rapid-fire information, diverged significantly from the viral claims. Despite persistent allegations and calls for severe penalties, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) did not sue Bad Bunny, nor did it levy any fines against him, the NFL, or NBC for his performance. The widely reported $10 million penalty was a complete fabrication, debunked by multiple fact-checking organizations. This article dives deep into the events, the political pressure, and the ultimate findings of the FCC investigation that cleared the Puerto Rican superstar.

Unpacking the Controversy: Lawmakers' Outcry and the "Illegal" Halftime Show

The genesis of the controversy traces back to the powerful voices of Republican lawmakers, most notably Florida Representative Randy Fine and Missouri Representative Mark Alford. Following Bad Bunny's Super Bowl halftime performance, these officials publicly decried the content, labeling it "disgusting" and "illegal." Rep. Fine, in particular, was vocal on social media and in official letters to FCC Chairman Brendan Carr, demanding "dramatic action."

Fine's complaints centered on what he claimed were explicit lyrics and vulgar content exposed to "130 million people and children." His posts and letters often quoted lines he attributed to Bad Bunny's performance, pushing for fines and broadcast-license reviews against the NFL, NBC, and the artist himself. Rep. Alford echoed these sentiments on Fox News, admitting he didn't speak Spanish but insisting that "a lot of information" had surfaced about the lyrics' offensive nature.

This political pressure was not isolated; it was part of a broader "culture war" criticism targeting the Super Bowl halftime show's content and language. The context further reveals that FCC Chairman Brendan Carr had previously shown receptiveness to conservative complaints, which likely emboldened lawmakers to pursue regulatory action, even if the legal grounds appeared tenuous. Their formal requests and public outcry painted a picture of a regulatory body under immense political scrutiny, tasked with scrutinizing one of the biggest live television events of the year.

The FCC's Verdict: No Violations, Case Closed for Bad Bunny

Amidst the political clamor and the swirling rumors that Bad Bunny was sued by the FCC, the agency initiated an investigation. This was a crucial step to ascertain whether any broadcast indecency rules had been violated during the highly-watched primetime event. What the FCC discovered, however, starkly contrasted with the lawmakers' accusations.

News outlets that reviewed the broadcast in detail, alongside the FCC's internal investigation, noted several key findings:

- Misinterpreted Lyrics: Many of the explicit lines cited by critics were either literal translations of Spanish lyrics that were not performed on air, or they were mumbled, cut off, or modified during the roughly 13-minute set. This directly undermined claims of overt profanity in English.

- Cleaned-Up Act: Surprisingly, the FCC found evidence that Bad Bunny had actually "cleaned up his act" for the Super Bowl. The artist, known for his edgy and uncensored style, had made conscious efforts to present a more family-friendly version of his music for the broadcast.

- Thin Evidence: When the FCC obtained official translations of what Bad Bunny *actually* said during the performance, the evidence of rule violations appeared "thin at best." The agency concluded there were "zero violations."

- Debunked Fine: The widely circulated claim of a $10 million fine was explicitly debunked by fact-checking organizations. There were no official reports or notices from the FCC indicating any penalty against the artist, the NFL, or NBC. The calls for fines were proposals and complaints, not completed penalties.

Ultimately, the FCC found no violations, concluding the investigation and effectively closing the case against Bad Bunny. This outcome was a significant blow to the lawmakers who had demanded "dramatic action" and a clear victory for artistic expression within the constraints of broadcast regulations. For further details on the FCC's specific findings, you can read more at Bad Bunny Cleared: FCC Finds Zero Super Bowl Violations.

Beyond the Headlines: Understanding FCC Regulations and Culture Wars

The Bad Bunny Super Bowl saga offers more than just a headline; it provides valuable insight into the complexities of FCC regulations, the power of public and political pressure, and the ongoing culture wars that often play out in the media. Understanding these elements can help clarify why such controversies erupt and how they are typically resolved.

FCC Enforcement Constraints: The FCC primarily regulates "broadcast indecency" during specific hours when children are likely to be watching (typically 6 AM to 10 PM). However, its authority isn't absolute, especially regarding live events and third-party content. Legal analysis often points to constraints on FCC enforcement for "fleeting indecency" – brief or isolated instances of offensive material. Furthermore, regulating content produced by private entities like the NFL for a halftime show presents unique challenges, with some commentators arguing the agency lacks clear authority to levy fines against performers for such content. This legal ambiguity made the congressional threats appear "legally weak" or "baseless."

The Role of Political Pressure: The situation clearly demonstrated how political figures can attempt to leverage regulatory bodies to push cultural agendas. While public complaints are a legitimate part of the FCC process, the scale and nature of the complaints from Rep. Fine and others highlighted a deliberate strategy to frame the performance within a broader conservative critique of "woke garbage." This highlights the importance of distinguishing between politically motivated complaints and actual legal violations.

The Spread of Misinformation: The rapid dissemination of the "Bad Bunny Sued By Fcc" narrative, complete with a hefty $10 million fine, underscores the challenges of misinformation in the digital age. Viral posts often outpace official corrections, leading to widespread belief in unverified claims. This incident serves as a stark reminder of the critical need for fact-checking and relying on credible sources when consuming news, especially during high-profile events.

Artistic Expression vs. Broadcast Standards: The controversy also reignites the perennial debate about artistic freedom versus broadcast standards. Performers in high-stakes, live events often navigate a tightrope, balancing their artistic identity with the need to adhere to the stricter rules of network television. Bad Bunny's decision to self-censor for the Super Bowl shows an awareness of these constraints, even if critics were unwilling to acknowledge it. For a deeper dive into how political pressure failed to sway the FCC's findings, consider reading Political Push Fails: FCC Exonerates Bad Bunny Super Bowl Show.

Conclusion: A Clear Verdict Amidst the Noise

In conclusion, despite fervent public and political pressure, and the widespread but erroneous belief that Bad Bunny was sued by the FCC and fined $10 million, the reality is far simpler: Bad Bunny was definitively cleared. The FCC’s thorough investigation found no violations of broadcast indecency rules during his Super Bowl halftime performance. This outcome not only vindicated the artist but also reinforced the integrity of the FCC's regulatory process against politically charged claims. The episode serves as a powerful illustration of how misinformation can spread, how political agendas can attempt to influence regulatory bodies, and ultimately, how factual investigations can cut through the noise to deliver a clear verdict.